Slay Like Sergio

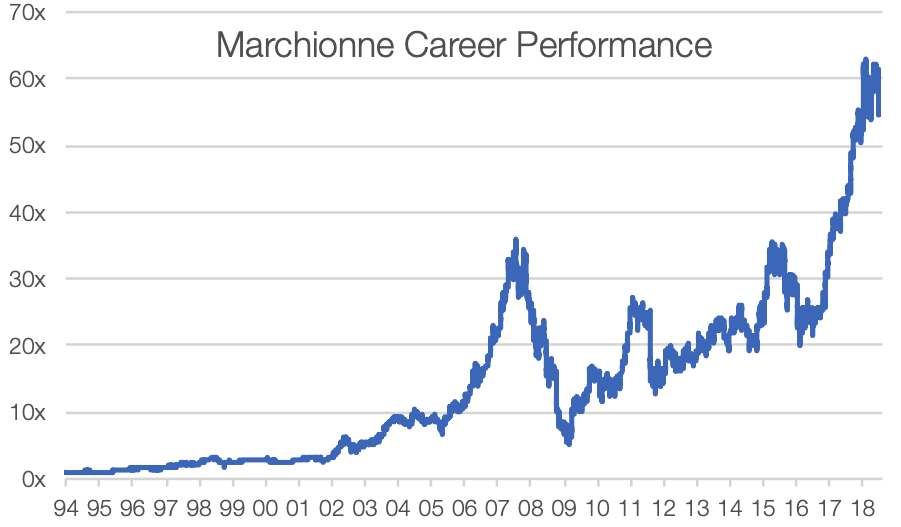

Sergio Marchionne's secret sauce that helped him turn €4B to >€100B and counting...

My Story With Sergio

“I’m not a believer in the automatic recurrence of the past. The future is always built.” -Sergio Marchionne

It's only fitting that I start this substack by profiling one of my personal heroes that I was fortunate enough to get to know briefly before he passed away. That's the thing about Sergio Marchionne, if you ever met him -- maybe even once -- you have a story about Sergio.

I've met dozens of people from random disconnected parts of the world, not even the Fiat universe, that all claim they lost a "great friend" when Sergio passed six years ago. That was the secret and the magic of Sergio, he connected with everyone on a human level.

While this was clearly due to innate skills and behavioral aptitudes, he wasn't always a great connector -- it was something he honed as he rescued shit show after shit show.

How many business meetings have you been in, where you came away feeling like you learned a bit about the world, psychology, philosophy, and also were in touch with the human spirit during the meeting? And then you also wanted to buy anything that person had touched?

During every meeting I was fortunate enough to have with Sergio (always a group meeting, for I am way too unimportant for him to have given me a 1x1), people would either come away mystified, confused, or as if they just were given the holy word of God from the top of a mountain in Jordan.

I was the latter.

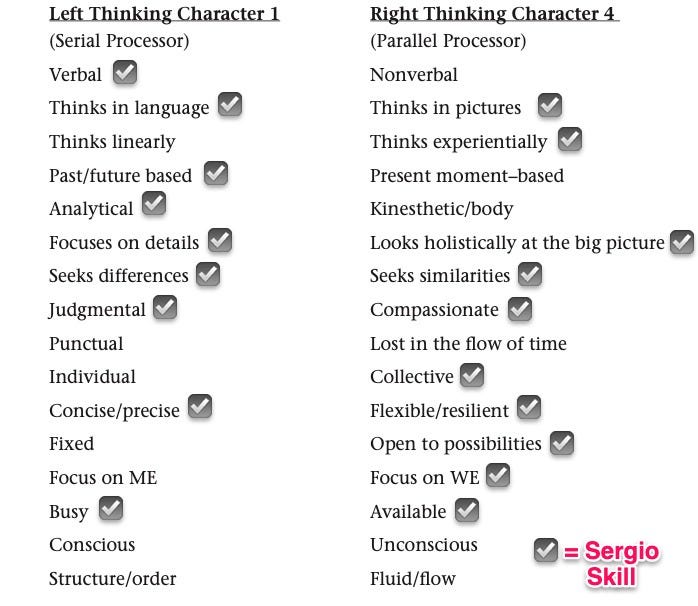

Who you were depends on what part of your brain you orient around -- for those who are left-brain dominant never cared deeply for Sergio, they never understood him, almost as if he spoke a different language. Because in the latter stages of his career, he connected and built from his right brain.

The first time I was invited by investor relations to meet him, I turned them down. My dad was on his possible death bed with a very bleak outlook from his cancer diagnosis. In fact, I got the bad news call from him while I was still in Europe, just having left Torino to visit Fiat HQ and the IR team -- which remains one of the best I've ever come across in my career.

Surely I couldn't leave my dad if he was possibly in his final days.

But my dad knew about Sergio. He had seen him on the news, I had played for him earnings call snippets where he answered his skeptics in a manner that made a few of the rare believers back in the day of 2012, rip their shirts off superman style. He was a gladiator fighting lions, tigers and bears, and we were all watching from the stands. At time it seemed like the underdog wouldn't pull it off. But he always did.

My dad found out about the meeting and then forced me to go.

When the Prime Minister Calls...

"All courses of action are risky, so prudence is not in avoiding danger (it's impossible), but calculating risk and acting decisively. Make mistakes of ambition and not mistakes of sloth. Develop the strength to do bold things, not the strength to suffer.” - Niccolo Machiavelli

Goldman Sachs was hosting a few investors to meet the big man in Auburn Hills, in the abandoned board room at Chrysler's HQ. Very few showed up. It was so embarrassing, that IR kindly invited little old me, with I think maybe $4 million in assets under management, to the meeting back in the dog days of summer 2012.

Half of the empty room was short Fiat stock. It was in the middle of the Grexit Crisis, and he had just finished a call with caretaker Italian Prime Minister Mario Monte who was trying to rescue his own country from a financial crisis. Do you ever wonder who government leaders call when they have their backs to the wall and can't rollover their debt?

They call people like Sergio.

He had already saved a group which was once nearly a quarter of Italian GDP from the brink of bankruptcy -- and then did it again with Chrysler. I remember thinking earlier in my career when I was investing in Ford debt & equity that Chrysler would be liquidated -- it was beyond hope. There was no value in it, after Cerberus milked it for its cash and stopped investing in product for years.

I was wrong, because Sergio existed.

That hot day in Auburn hills in July of 2012, Sergio was so stressed about the situation not only Italy, but Fiat itself was in, that he told the group he was sorry that he was late, but he drove >120 mph (>190 kmph) down a Michigan highway in his Ferrari to meet us. The Prime Minister called. The skeptical hedge fund audience could wait.

I would later learn that in order to burn off the heaps of stress that his multiple CEO roles would throw on him, that he would take a Ferrari on the race-track and drive as fast as humanly possible.

I prefer meditation. Sergio preferred a prancing pony.

What he was inadvertently doing was a brilliant trick on the mind -- which we'll go into later.

Back in Auburn Hills, the meeting lasted a full afternoon, and while I loved him on conference calls, and in public, it was next level Sergio. He was always a truth-teller, but behind closed doors, he would name names and call BS where he saw it. He was ruthlessly honest. And he wanted us to be -- he seemed to respect the critics more than the rare cheerleader. He didn't want to know what you liked, he wanted to know what you were afraid of, where he and his gladiators could do better.

The brave attendee asked what he would do if Italy exited the euro-zone and circled the drain? (I'm paraphrasing, because my 12-year memory isn't as clear as Sergio's would still be.)

"We distribute Ferrari to investors, and possibly distribute the stake in Chrysler (it was still only 58%-owned by Fiat). This house can't keep subsidizing the other side of the Atlantic forever. Eventually it may go bankrupt, but not before shareholders are holding 'multiple pieces of paper.'"

It was a mic drop moment.

There was no follow up response to that. I remember thinking, is that even possible? The answer was quick -- they already did it. No creditor approval was required for the spin of CNH Industrial, because of Fiat's heritage -- even though it was "junk rated debt," the house continued to issue debt under an investment-grade bond indenture. Those contracts allow for much more lenient distributions of cash and assets to equity holders. That was quite a wrinkle in the story.

Not even the bulls would believe it-- it was such an incredible assertion to believe back in 2012 when Italy didn't know if it could refinance its massive debt load, which was third largest in the world as a percentage of GDP.

The Pitch

"Unions and Low Margins and Italy. Oh my!"

-Opening Words to my First Write-Up on Fiat

That day in Auburn Hills galvanized me. I know a lot of people came away in disbelief that he could do what he told us, and that was a very common refrain he had his entire career. Most people chose to think he was just "not credible." Most portfolio managers, particularly those in Europe, didn't like Sergio. He was too honest. He didn't play by anyone's rules. That was unpredictable in their eyes, and over-promising to the market is always a recipe for disappointment.

And it proved to be at times with Fiat.

No matter. A new online financial community, SumZero, was running its first contest for the best ideas. I had spent a year already owning the stock, and had been building the most detailed financial model of my life (which I would later learn was largely a waste of time). Most of those rows didn't matter -- as the only thing that mattered was the will and the ability for Sergio to spin Ferrari.

But it gave me conviction. Fiat was trading sub €4 per share, and I thought it would be worth >€30 in the next few years. I explained why in the write-up you can still download here.

When the finalists were announced, I remember getting dizzy when I saw my name pop up. The other two ideas, pitched by two fellow analysts who I remain friends with to this day, pitched 30 or 50% upside on theirs. No one dared pitch an idea with nearly 10x upside. Typically people massage their aspirations for fair value to make it seem more believable. But Sergio didn't do that -- and I've never understood that.

It was a pitch that would have made Sergio proud.

It wasn't mediocre. It was bold. It was worth getting out of bed for. It was worth leaving my dad in his hospital bed for. But it was believable with a guy like Sergio at the helm.

The finalists were invited on (hilariously) Fast Money on CNBC to make their pitch. I pretty much blacked out, but said something mildly intelligent about "Fix It Again Tony," (FIAT) and its leader. Thankfully, CNBC.com's archives don't go back that far, so you can't audit me.

But I felt like I had an edge. Sergio told me and a few other people to our faces that we would "hold multiple pieces of paper" in the worst case scenario. The risky asset was actually without risk.

Those don't come around frequently in an investing career, and when you find them you go BIG. We invested 8% of our portfolio in the company. That's a decent-sized position for many portfolio managers, but I clearly wasn't like them. I was managing our investors' accounts from a temporary rental apartment next door to MD Anderson in Houston.

It was there, at that hallway desk, that I saw Fiat in free-fall shortly thereafter. Wondering what was happening, somehow I learned that one of the most prominent fund managers (with to this day, one of the best track records of all time), told investors at a conference to short it, as it was a "crappy company."

Clearly he knew what he was talking about, and had an incredible track record to prove it.

My investors started calling -- "are you sure about this Fiat?"

Honestly, yes, but wait, maybe no. My confidence was shaken. Who was I to believe in someone that I've met only once? But wait, I was a trained credit analyst. Wasn't the only thing that mattered the ability for the company to spin Ferrari? Fiat and Chrysler just represented additional upside. But the value was backed by Ferrari. Or was it?

I at least thought so. After getting my bearings and re-underwriting the work, we doubled our position in both Fiat & its holding company Exor to 17% in early 2013. Betting big on Fiat and Sergio came with a lot of setbacks, but I wasn't yet done buying shares on pull-backs.

It's easy in hindsight to write about successes, it makes you feel good. But what I find more interesting isn't the conclusion, but the bottom of the ocean climax -- when the hero lost his way and almost didn't make it back. I know a few believers that were shaken out of the trade. It was hard to ride a roller-coaster when your career was on the line.

To me, the more interesting moments in anyone's career are the dog days when you wonder if it's ever worth the effort. How do you trudge through and keep believing when you're constantly faced with people telling you to give up.

Men in the Arena

“It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.” -Teddy Roosevelt

While it was hard to bet your career on the Fiat rolloercaster, it was 10x more rigorous actually working for Sergio. These were the men in the arena that were getting bloodied by lions, tigers and bears on a daily basis. Somehow Marco in investor relations really liked me, or maybe there was truly no one else that cared enough, but I kept getting invited to events.

I remember at a private dinner with CFO Richard Palmer, he admitted that nearly every manager that committed to performing for Sergio's incredibly high standards ended up divorced. There was no work-life balance. Work was life. It wasn't for the faint of heart.

But while Sergio had incredibly high expectations, he gave of himself to his managers and his organizations. He would dedicate two entire months of his year to personally reviewing mid-manager performance of quite literally thousands of managers across the many organizations he oversaw: Fiat, CNH, Iveco, Ferrari, among many more. The group was, after all, responsible for a quarter of the Italian economy in its hey day.

He was there to grade them, but also to offer them advice. He was not only the boss with perhaps the highest expectations -- but he was also the world's best career coach.

He truly cared about people.

When John Elkann, the chairman of the group, expressed his sympathy for Sergio's irreversible decline at the end of his life, he noted:

"What struck me about Sergio from the very beginning, when we met to talk about the possibility of him coming to work for the Group, even more than his management skills and unusual intelligence, were his human qualities, his generosity and the way he understood people."

But he wasn't always that way.

Eager to start building his career, he skipped typical adolescence and quit high school so he could begin working at the ripe age of 16. By 18 he was already a branch manger of a Savings & Loan bank, but as any 18 year old, he was "a horrible shit," in his own words. He was able to differentiate himself, but at a very high cost -- his authoritarian style at the time got results, but "the price was too high."

It was a fundamental core learning at the beginning of his career -- he couldn't treat people as cogs in a machine. They they were humans, and so they were emotional beings that also think (as opposed to thinking beings that also have emotions).

While he later went to school and finished his numerous degrees, this pull between working and education was always a core internal tension that he held. He would frequently talk about wanting to be a philosopher, or a theoretical physicist, but then one of his half dozen phones would buzz with some sort of crisis that needed his attention. At the end of his life, he told his "affectionate stalker" Tommaso Ebhardt that he'd really like more time to think. His executive roles never allowed him to think about thinking -- but he was an avid student of the meaning of life, and the functioning of the universe.

But he never had this kind of time. Time was his enemy -- fairly ironic for someone who wanted to study theoretical physics. He gave his everything to the many organizations that counted on him, but while he was the center of the Fiat-CNH-Ferrari Galaxy, he was always trying to push decision-making and autonomy to his team.

Here's one of the many dichotomies that Sergio would exhibit throughout his career -- he was constantly in touch, constantly helping his managers make decisions, but then he would push as much responsibility as he could down the chain. He wanted to remove layers between him and every employee at the group. He wanted the organizations to feel the same sense of purpose that he clearly had. But it also came from humility. He always felt like such an underdog that he was constantly trying to build strong teams around him.

"At the beginning of my career, the CEOs, the managing directors, represented something mystical to me. I believed there was something in these people that made them special and I was convinced I did not have those qualities in me." As Tommaso Ebhardt quoted in his terrific biography of "the sweater man."

A Partner In Crime

"Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face." Mike Tyson

To himself, he was not a great man, only someone who was humble enough to ask stupid questions. This humility is key, for while Sergio had a very clever bottom brain, also called E.Q. (Emotional Quotient) or street smarts, humility is always the key to ensuring that he never operated from the bottom brain ego.

How do we know Sergio had a very high E.Q.?

Because he was an expert negotiator. He was so good, that none of his peers in the industry trusted themselves to negotiate with him. He was that good. No one would face him. His "street fighting" skills were always on full display not just in boardrooms, but on earnings calls, where we would constantly go toe-to-toe with the skeptical banking audience, largely from London.

While most executives, scratch that, most mortals, approach any recorded call with the public, or televised appearances, with sincere anxiety and a heavily edited script, those with strong bottom-brained survival skills don't need a script. The epitome of top brain vs. bottom brain would be any of the presidential candidates using logic & rational answers to try and win a hopeless debate against bottom-brain master Donald Trump. I know in using a political example, I may turn off people, but even his supporters can't deny, Donald has a pretty remarkable ego. In turn, he is very good off-script -- especially when debating his opponents that have talking points, scripts and pre-planned messages.

The bottom brain, not just survival and fight-or-flight, but the emotional parts of our brains, is an incredibly important alibi in any value creators' quest to build something of meaning.

In short, the ego is not the enemy -- the ego if our alibi. It's our partner in crime.

The reason is, consumers, voters, or stock traders all make their decisions from this part of our brains. To have a strong ego is to identify with the very person that you need in order to make your company, campaign, or earnings call a success.

However, as the popular narrative suggests, via Ryan Holiday's great work Ego is the Enemy, once we operate from this domain of our minds, we consume value rather than create it. This survival mechanism of our brains, and the behaviors and emotions around it, are not capable of strategy. The bottom brain cannot create, and it can't invent. It can't put together a coherent business plan, but it can translate your creation, your plan, or your business to the counter-party. "It takes one to know one," and for Sergio, he had an invaluable partner in his quest to build something meaningful. But it on its own can't build. It can only translate that blueprint to an emotional language that more people can understand.

Sergio's Evolution from Bottom to Top

"In times of great stress of adversity, it's always best to keep busy, to plow your anger and your energy into something positive." Lee Iacocca

What does all this commentary on the ego and the emotional brain have to do with Sergio?

Because in the first post introducing this series, and the upcoming book, the question I ask is not what these Builders did, not even how much value they created (though that's clearly the headline grabber) -- but rather, how they did it.

Sergio started as a manager of a savings & loan bank. He was authoritative and rigid. When he finally did go back to school, he got undergraduate degrees in philosophy, then commerce. We went on to get graduate degrees in both business and law. Immediately, we see him evolving from a ego-driven initial attitude to one that embraces skillsets from both sides of the intellectual brain --- philosophy with the abstract and conceptual thinking, and business and law with the more analytical, language-oriented and mathematical skillsets.

The fact that he had 2 undergraduate degrees and 2 graduate degrees -- with nearly completely different skill-sets attests to the claim that Sergio had a balanced brain -- top, bottom, left and right.

In Sergio's earlier part of his career, he pursued mostly financial-oriented roles. First an accountant at Deloitte, then moving onto an industrial packaging company as the controller. He mainted the books and the accounts, a left brain activity, but he was able to find meaning behind math -- a right-brained activity. Whereas mathematical functioning is largely a left brain oriented tool, Sergio's accounting roles quickly morphed into business development roles, where he was part of the M&A discussions of consolidating industries.

"His biggest negotiation talent is that he is able to put himself completely in the shoes of the person on the other side of the table," said the owner of one of these consolidating businesses, Acklands. Sergio left Acklands to become the chief financial officer of a packaging group that was bought by Alusuisse in 1994. From humble Canadian beginnings, he always negotiated well for his companies and for himself -- for only 2 years after being acquired by a far larger Swiss group, he was promoted to CEO of the entire group.

While no earnings call transcripts survive, or none that I can find, it was here that he learned street-fighting skills with Wall Street. It's likely, given his already noted success in negotiations, that he was a natural at it. But effective netogitation isn't only an emotional skill -- it's a combined use of top and bottom brain together. MRI's taken of those undergoing negotiation tasks have indicated that emotional mastery is key, while utilizing feedback and input from our critical thinking top brains.

It's the same for facing the nearly always-skeptical audience on quarterly earnings calls. There were very rarely any prepared remarks, it was all "on the fly." When he was finally CEO of Fiat, he would routinely skip prepared remarks and immediately turn it over to his CFO to review the quarter. Of course, nearly all questions were directed at Sergio, and he would answer incredibly candidly -- and in ways that made it hard to retort.

As a dedicated Sergio fan, I would always get pissed about the constant fight he had with the skeptics -- and that they just didn't "get it."

But what I didn't realize at the time, is they were speaking a completely different language.

No, Sergio didn't speak Italian on earnings calls. He spoke from his heart. He spoke as a philosopher, as a theoretical physicist, as a manager guiding hundreds of thousands of people to rescue a usually pretty dire situation. He spoke from the perspective of someone who's faced the gates of hell and has brought his own mind and his team's back from it. He was more than a Builder -- he was a survivor.

He had seen failure, but he had over-come it. He didn't need to operate from his bottom-brain survival mechanism, because he survived and lived to see another day.

Just like a lot of Twitter today, the market and its skeptical analysts would speak from the bottom-left brain. It becomes obsessive with the survival mechanism dominating a lot of its behavior. As Jill Bolte Taylor profiled in Whole Brain Living, this part of the mind can get lost in its own world of skepticism, doubt and risk-aversion. Interestingly, it is disconnected from reality. Patients that have had the super-highways between the left and right brains severed have routinely showed that the left brain is completely disconnected from the real world reality. It is a super-computer, but it is very bad at understanding what is right in front of its face -- especially if it was new.

Source: Whole Brain Living

And Sergio was new. He was fresh. He was something that the auto industry hadn't seen -- since perhaps Lee Iacocca, who rescued Chrysler in the 1980s.

Where others saw a horrible situation, he saw opportunity.

But remember how he would blow off stress racing as fast as he could with his Ferrari? I think what was happening, is he would use the simulation of the emotional right brain through risk-taking, adventure-seeking, fearless activities, and would pull himself from the far gloomier world of the Stock Market, and the emotional left brain character described in the table above.

How perfect, then, that when he was battling with the shorts, and helping the Italian Prime Minister roll his debt in 2012, Sergio was constantly getting speeding tickets on the Michigan highway.

None Shall Sleep

"The greatest discovery of my generation is that human beings can alter their lives by altering their attitudes of mind." -Lee Iacocca

Sergio was constantly called on in his career to answer extremely challenging problems, and he did so by having some other gladiators that were in the arena with him. When he came into rescue Fiat from the brink -- with banks getting ready to hang a foreclosure sign on the front door -- he went to work very quickly.

He changed the culture by getting rid of bureaucratic decision-making. While he would blame bureaucratic Italian corporate culture -- frankly, bureaucracy is everywhere in the corporate world. It develops from processes and procedures that were devised long ago, and worked at one point in time.

But by 2004, the policies & procedures no longer worked. They were devised for a different time. Not a foreclosure moment. Bureaucracy, like most of society today, is left-brain oriented, and is therefore divorced from reality. Sergio spent his first few weeks interviewing thousands of managers, dismissing many of them after a quick 30 minute meeting. He would then promote believers and achievers sometimes three levels up in order to assemble the team he needed to reach for discontinuity and challenge accepted wisdom.

As he was quoted in the HBR Case Study, "He was looking for three characteristics: first, people with the willingness to risk and to participate in genuinely open communication; second, people with “operational leadership,” managers able to lead but also able to operationally do things; and third, people with less focus on their personal agendas than on the more general company agenda."

As he assembled a management team of direct reports that tripled in size, he removed a few layers in the organization between him and the line-worker. As he did it, he was re-assembling the group in real-time. He was assembling an airplane on the runway, as the group was long out of time to restore its competitiveness, portfolio and strategy.

Immediately the master deal maker flew to Detroit to present to GM's CEO, Rick Wagoner. A few years earlier, the two entered into a collaboration agreement where GM granted Fiat a put option to sell the business to GM a few years later. "Surely the Agnellis would never want to sell," must have gone through Jack Smith's head as he signed the agreement in 2000 to collaborate with Fiat to save on development and procurement costs in Europe & South America.

But in 2004, Smith's successor, Rick Wagoner, was no longer dealing with an Agnelli. He was dealing with a Marchionne.

And Sergio exercised the put.

He presented dire financial forecasts to Wagoner and the GM board of Fiat's medium-term future that was going nowhere.

While he was sounding the alarm bells in Detroit, he was furiously trying to recreate a company with few resources. When he challenged engineers to speed up the development of the new Fiat 500, they asked for 4 years.

When he challenged their assumptions, he got a lot of answers along the lines of "because that's the way it has always been done." He pushed back on all of those answers -- and found surprisingly little resistance to the plan to shrink a four-year development plan to 18 months.

But while he was challenging his new band of managers to bring new product and a new strategy to their core business, he was also trying to sell the dumpster fire to GM. And he had a legal right to it -- granted to Fiat back in 2000.

Months of negotiations took place, with many trips back to Detroit, until Sergio left with the check that he had in mind the whole time: $2 billion.

What did GM buy?

Nothing.

Wagoner spent $1.99 billion to not acquire the dumpster fire of Fiat, and frankly, he wasn't wrong to do it.

No one believed in Fiat. Many former managers that Sergio dismissed were dismal about its prospects.

But his new team of "kids," as he called them weren't.

Upon the closing of the agreement with GM, Fiat returns to profitability. He sends his executive council an email quoting the philosophy of the African ubuntu, which roughly translates to "I am because we are."

"The shape and meaning of Fiat will depend on the aspirations and the commitment of those who lead it. It's an extraordinary responsibility, but there's nothing better in life. For my party, as your leader, I can tell you one thing. I see you. I'm glad you're here."

As Fiat was closing its accounts for 2005 in early 2006, its hometown of Turin was hosting the Winter Olympics. As Ebhardt points out in his book, Luciano Pavarotti's rendition of Nessun Dorma "powerfully emanated from the communal stadium, awakening the pride of the people of Turin and Italians around the world, while SM worked day and night to revive the fortunes of Lignotto."

How fitting that Nessun Dorma, or "None shall sleep" was the anthem that Torino chose to open up the ceremony of the Olympic trials. Sergio and his managers had to skip a normal sleep schedule in order to save the "Italian institution."

He would emphasize earlier in his career in a Swiss TV interview, "A great manager must work twelve, thirteen, fourteen hours a day. For the example he sets, which is worth more than all the hours of work." On his over 40-days he spent traveling across the Atlantic Ocean, he wouldn't sleep for 24-hours, instead preferring to play poker and talk strategy with his direct reports.

He would never ask anything of his managers that he wasn't willing to do himself. And that's how he would build a tremendous loyalty between he and them -- so much so, that as Palmer mentioned -- they'd follow him through divorce procedures in order to answer the call.

If you haven't listened to Nessun Dorma recently, you should put it on to feel the emotional climax of the song that foreshadowed the win coming up in Turin (click here for Spotify and click here for Apple Music).

A year after the Olympics, Sergio's team relaunched the Fiat 500 -- an iconic car and an iconic update. They hadn't slept, but they had bent time in their favor.

It was July 4, 2007, the fiftieth anniversary of the launching of the original 500. 100,000 people attended the fireworks and launch ceremony along the Po River, with 7,000 VIP guests in attendance.

The launch ceremony was unlike anything that the car industry had seen before. It was designed and planned by the same artist that created the Olympic opening ceremony that blared the song Nessun Dorma just over a year earlier.

It was a dramatic moment that showed in spectacular format what a couple dozen managers could do in less than three years. Fiat was not only profitable, Marchionne, an avid Apple fan, believed that the Fiat 500 was his iPod moment and that Fiat was on its way to becoming the scrappy Apple of the car industry.

That same day, Sergio airs a new video for the workers of Fiat.

“Life is a collection of places and people that write time. Our time.

We grow and mature by collecting these experiences.

These are the ones that end up defining us.

Some are more important than others, because they form our character.

They teach us the difference between what is right and what is wrong.

The difference between good and evil.

What to be and what not to be.

They teach us who we want to become.

In all of this, some people and some things bind to us in a spontaneous and inextricable way.

They support us in expressing ourselves and in self-realization.

They legitimize us in being authentic and true.

And if they really mean something, they inspire the way the world changes and evolves.

So, they belong to all of us and to no one.

The new Fiat belongs to all of us.”

All of us.

They were all-in, from the top management to the line-worker.

The 500 launch was not just a crowning achievement moment for Fiat and Sergio, but as he wrote to employees, it taught "us who we want to become."

The industrial plan, which he built in only 8 weeks upon assuming the helm of a completely new set of industries, was finally translated into an emotional, evocative, event that connected with everyone in Italy. It struck a chord everywhere, not just at Fiat. Finally employees were proud to work for the company -- and customers were eager to purchase a new Fiat again.

It was the evolution of a left-brain industrial plan to a right-brained, emotional and creative plea to all of the company's customers, employees, and even investors, to give Sergio and his team a chance to win. He was able to translate math and numbers into fireworks, songs and one of the most iconic auto designs of all time.

And, as the song Nessun Dorma ends, "I will win. I will win."

The accountant and negotiator had evolved into something much, much more -- more akin to a general on the battlefield, leading his troops from the front lines. His historical focus on capital and investors had yielded to honoring the dignity of the line workers and the engineers.

As he later reminded investors in a bold manner, he never forgot capital. It was the life-blood of all his efforts. It was anchored by Chairman John Elkann and the stability his family control gave the group.

But the most impressive part of Sergio -- the one that could relate to each person he spoke to -- would be the leader, the outsider, the one who asked difficult questions, and to paraphrase his favorite company Apple, the one who would "think different."

Confronting Adversity

"As one observer put it, Chrysler is most likely to be liquidated for 3 sticks of gum and a roll of pennies." -Sergio Marchionne

Even when he was celebrating the new Fiat, the new culture, the new 500 and the transformed fortunes of the group that three years earlier was on the brink of bankruptcy, Marchionne was sober in confronting adversity.

A year before the global financial crisis emerged, he was looking to collaborate with Chrysler in a similar manner to how Fiat originally tried to collaborate with GM. In fact, he was always looking to collabrate. In stark contrast to his peers, he viewed his competitors as examples to look up to, and as potential friends. Before he sealed the deal to take control of Chrysler, he forged several strategic alliances with Ford (2005), Tata (2006), SAIC (2006), DaimlerChrysler Truck (2007), Chevrolet (2007), and Severstal Auto (2007).

In many ways, while he was not an Agnelli, he emulated the original founder of Fiat - Giovanni Agnelli, who had a great friendship with Henry Ford. He borrowed Ford's idea of the assembly line, and took it to Italy. While Ford is credited with inventing the assembly line (a popular delusion we'll discuss in the book), Agnelli beat Ford to the market with his first commercial car.

Marchionne never had animosity towards any competitors, and in fact, he had envy of how well VW converged platforms, how well Tavares (PSA) managed the turnaround in Europe and jealously watched Ford's margins on the F-150 converge to the 20% level. He was inspired to improve his performance when he saw a competitor doing something better.

With Chrysler, he was looking for cost synergies, particularly in Latin America. During those discussions, he would ask its CEO, former GE and Home Depot executive Bob Nardelli, what his plan was in case the US auto sales were to collapse to 10 million.

Nardelli repeatedly responded that such a drastic contraction was not possible.

I remember that being the refrain of executives that lost their jobs in 2008.

Sergio had been wondering about such a disaster scenario for a long time. Over a year after he asked the Chrysler executives that question, they were gone. Auto sales had fallen below the dreaded annualized level of 10 million. And he wasn't negotiating with Nardelli.

Rather, he was negotiating with the White House.

He was the only one that showed up.

No one else did. At the time, Fiat was still enjoying the dividends from its industrial plan, the successful product launches and the relative stability of the Italian market resulting from the fresh lineup. Sergio also had the stability of the Agnelli family, and John Elkann.

Having the stability of John's support during a time when everyone else was operating from the survival mechanisms within their brain freed Sergio to be open to possibilities as opposed to fixated on the fear-based and cautious approaches that all of his competitors were operating under -- even those that had a family controlled board.

Thus, while the entire world was over-come with bottom-brain survival instincts, John allowed Sergio to operate from his intellectual brain -- where he could press his strengths.

Source:Whole Brain Living

Operating from the rational part of our brains, ironically enough, allows us to confront adversity more readily and easily. When we operate from the brain stem, the emotional part of our brains, human nature has routinely shown it avoids loss at all costs. It even avoids the news of a loss -- witness most people avoiding to check their investment accounts during 2009 -- the very time Sergio was confronting the adversity and addressing it head on.

He would always want bad news to travel fast so he could deal with it -- not avoid it. A year before the financial crisis, he was already worried about a potential that Chrysler's former management team dismissed as "impossible."

When the unthinkable happens, almost everyone stops thinking.

Very few people can remain open to new information, and address the situation head on.

Imported To... and then From Detroit

"You see, it’s the hottest fires that make the hardest steel.

Add hard work and conviction,

And the know how that runs generations deep in every one of us.

That's who we are. That's our story."

Not only was Sergio the only one at the negotiating table at the rescue of Chrysler, but his trademark incredible negotiation skills -- the combination of EQ & IQ -- were on full display. While it would take years for Fiat to buy out the debt and equity of Chrysler, he would formulate the buyout conditions and clauses before he would agree to go to work.

At some point, the negotiator on behalf of the White House, Steve Rattner, accused Sergio of getting a deal that was too generous. He asked for Sergio to put some capital into the initial transaction. As Sergio later recalled:

“You have to put your skin in the deal,” Rattner insisted. “You have my skin. I give you everything I have: I give my technology base, my leadership and so on,” I answered. I was ready to risk my career, my reputation, the time of the House [FIAT]; I was not going to risk the financial stability of FIAT. If I failed, FIAT is gonna survive. I was expendable; FIAT was not.”

It wasn't just a negotiating tactic -- it was real. Sergio would not just put his skin in the game, he would put his soul in the game. It was apparent to every Chrysler worker, as he addressed them in the headquarters lobby, next to the Fiat 500 that not only saved Fiat, but earned him the initial stake of Chrysler by contributing its technology to gas-guzzling Chrysler.

It was deja vu all over again. Only five years after he pulled rabbits out of the hat to save Fiat, he had to do it again - only this time, there was no $2 billion check from GM. The stakes were higher. The American taxpayer had bailed out Chrysler, and morale in Auburn Hills was at rock bottom. Sergio used the same concept that worked so well to rally the Fiat managers around the cause to save it, and with it, connected directly to the demoralized workforce of the orphaned automaker in Detroit.

"The Great Man has been replaced by Great Groups. . . .

Among native people in Africa below the Sahara, the spirit of ubuntu is pervasive. The word itself is part of a longer expression, umuntu ngumuntu nagabantu, which translated literally from Zulu means “a person is a person because of other people.”

When you function in such an environment, your identity, what you are as a person, is based on the fact that you are seen and acknowledged by others as a person. It is reflected in the way in which people greet each other. The equivalent to “hello” is the expression sawu bona, which literally means “I see you.” The response is sikhona, “I am here.”

The sequence of the exchange is important: until you are seen, you do not exist. The implications of these cultural norms are significant. In the western world, we would think nothing of passing by someone and, pressured by work and other commitments, not greet him. In the world of ubuntu this would annihilate the existence of another: the acknowledgement of the other is what makes him or her a person. Without it, he or she is nothing.

And so as we try to build the Chrysler Group into a Great Group, our roles are to approach this daunting task with the mutual respect and openness that is embedded in the spirit of ubuntu. The Chrysler Group will take its shape and its meaning from the aspirations and commitment of the people who make up its leadership.

It is a heavy responsibility, but there is no better in life. From my end, as your leader, I can simply tell you that: I see you. I am glad you are here. Thank you all."

Sergio would abandon the top executive floor of the Chrysler headquarters building, and locate his desk in the middle of the engineering floor. He needed them to compress timelines and to launch new product. It had been a decade since Chrysler meaningfully invested in new product, and if was to break the discounting behavior of the past -- they very past that brought it to the brink -- it would start with refreshed product.

When the Italians came to revamp the product line-up, it was the first time that Jeeps would carry a truly premium fit and finish. My mentor Wally bought a 4-door Wrangler, and for the first time in Wrangler history, it was worthy competitor to the adventurer's holy grail: the Land Rover Defender.

The Chrysler Sebring also received an updated look and a premium Italian-inspired interior. Just like Sergio translated his industrial plan to an emotional launch at the 500, with each super bowl, he spotted an opportunity to redefine Chrysler's brands to its largest audience.

In the 2011 spot, the "Imported from Detroit" commercial not only set records, and won innumerable awards, but it also reflected the journey of Sergio and his team. It's an underdog's story of keeping your head down, working hard, and creating something of meaning. It was not just Sergio's story, it was not just Fiat's story, but it was now Chrysler's story.

The commercial produced "something that I've never seen in automotive history," as Sergio told a small group of investors. It was practically the same car, with a face lift, a new name and some leather-stitched interior.

Sales more than quadrupled.

It was the epitome of translating an industrial plan to an emotional appeal that would open wallets. The rebranding and minor face-lift would have gone nowhere without appealing to car-buyers' emotions. The commercial did that and so much more.

It was also fundamental to changing Americans' opinions about Detroit. Whereas in 2009, the Detroit dialog was all about "bailouts" and "union entitlement," its come back was palpable, and there was a new interest in buying domestic cars.

That year, Chrysler repaid all government loans, and Fiat continued its creeping takeover of the group through sweat equity, call options, and negotiation.

But investors in Fiat would ignore nearly all of the progress that Chrysler was achieving, since Fiat didn't own 100% of it. It couldn't access its cash, its cash-flow, so for the short-term oriented crowd, it was literally worthless. Regardless of the market ignoring it, Sergio would keep pressing his advantage and would push new product and new markets for the largely American brands.

Yet, Sergio had promised capital markets a few years before that he would invest in new Fiat and Alfa Romeo models. But with the Italian and European market taking out global financial crisis lows and heading much lower -- Sergio would redirect that capital and effort over to Chrysler's products.

The market further hated this.

Most organizations want their best executives to fix the "broken" parts of the organization, instead Sergio would put his best people on the brands, products and regions that had the most potential.

But Sergio had a plan all along.

A New Year, a New Company

“High expectations are the key to everything.” -Sam Walton

January 1, 2014. I'll never forget it.

I was on the New Jersey turnpike with my family, in the backseat, as I gasped, looking down at my iPad. "Fiat agrees to buy VEBA's 41.46% stake in Chrysler for $3.65 Billion."

The ignored asset could no longer be ignored.

What was even more remarkable about that day and that negotiation, is that more than half of the price tag was paid with Chrysler's own balance sheet -- the balance sheet that Fiat could never access.

While it took a couple extra years than what the market wanted, Sergio was able to finish the deal at less than 10% what Daimler paid for Chrysler less than two decades prior to that day.

He was defiantly patient in not raising his takeout price for the minority stake in Chrysler, owned by the UAW’s healthcare trust. Fiat would end up acquiring Chrysler at 1.1x 2013 EBITDA, or basically just over one year's worth of cash-flow.

I don’t believe a take-out has happened at that price in the history of corporate finance. Sure, maybe someone can pull enough synergies from a deal to make a price equally attractive, but to transact on historical fully-baked financials, and not pay >5x is unheard of. Sergio could have settled for 4x, or 3x. But he got it at 1.1x because he knew he could.

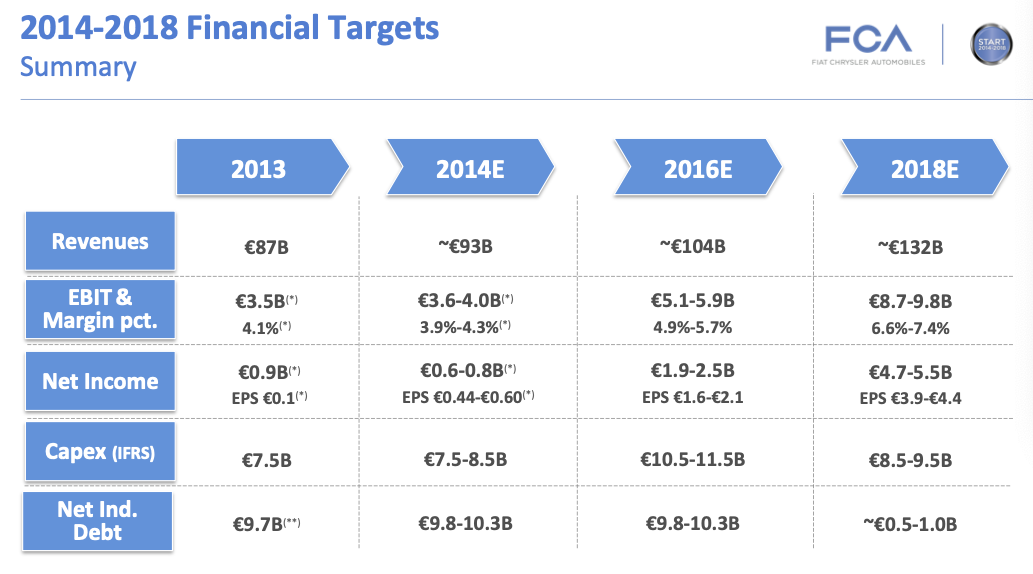

That day, Fiat Chrysler was born, becoming the 7th largest automotive group in the world. From the scrap heaps of two near defunct organizations, a global group had been created. It was time for Sergio to give another industrial plan to the market, where he would unveil his most ambitious targets yet for the group.

No one believed him when he said he would 5x net income, and bring wholesales from 4.4 million to 7 million. The high aspirations actually backfired, with the stock closing down nearly 10% on that day in June 2014.

Source: FCA's 2014 Industrial plan

Again, here was Sergio talking about the possibility of what could be to the Wall Street audience that only cares about what has already happened -- and what could go wrong. These were two different languages.

To the left brain, particularly bottom-left brain, the right brain voice of possibility is actually a turn-off. Sergio's introductory comments were backed by... wait for it... pictures.

No graphs. No charts. He was speaking in visuals, it was classic Sergio.

When the CFO finally delivered the spreadsheet, it was seen as non-credible.

The day was a disappointment to most, and for the believers, seeing the stock close -10% that day, it was dissolution. This was supposed to be a big day. A great day. In fact, it was greeted with a loud thud.

That day, Sergio put his money where his mouth was, and he bought more shares, along with Elkann, who joined him in defiant protest against the market reaction.

Sergio was to dedicate some time that evening to the few buy-side investors that showed up. Even fewer actually showed up late in the evening, so it ended up being the small group that I photographed at the end of the waiting area outside of the Auburn Hills board room.

As Sergio lit a cigarette in the non-smoking board room, he opens up with "Ok, what did you not like about the plan?"

This is the only CEO I know that opens with immediately embracing the negative.

"It's not believable" decried one brave investor.

"I'm paying my people on these targets. If we don't hit these targets, my people aren't getting paid," he would quickly retort.

As Tommaso Ebhardt quoted in his biography, he would later acknowledge that not every line item of the plan would get hit, but it didn't matter.

"The targets are the targets, but even I miss them by say 10%, I would be as happy as the puppet from the frozen vegetables commercial. We will never do the exact numbers, somewhere they will be worse and in some other business, better, but the fundamental question is whether we will be able to sell seven million cars, and above all, make the profits we have predicted."

That wasn't what analysts want to hear. They want to hear conservative, precise figures. They want you to always over-deliver. They want low expectations that they know you can beat.

But low expectations get you exactly nowhere. Sergio's peers were very good at setting low expectations. But they were also very good at getting nowhere.

Sergio's big dream was to take over the very company that paid him $2 billion to go away a decade earlier: GM. But neither GM's CEO nor its board was willing to negotiate. Mary Barra wouldn't even pick up the phone. By the time 2014 rolled around, Sergio's negotiation skills were now well known around the industry and the corporate world.

Perhaps she didn't trust herself to negotiate with the master poker player. But what does that say about the CEO, if they don't trust themselves to negotiate with a CEO that has a track record of making mergers and collaboration initiatives work?

It says that you care more about yourself than the organization you work for.

Or perhaps it says that you are comfortable in your left-brain fixed world as opposed to the growth-oriented and collaborative right brain. Your investors and your board will be comfortable in the left-brain, analytical, precise and organized world.

But that world is disconnected with reality.

And it was not the world that Sergio and Elkann lived in. Sergio did not have a board that would just "say yes," to whatever he said. In any board where Sergio served, there were active debates. According to Ebhardt's biography, there was even a controversial secret plan to go hostile on acquiring GM with debt and cash in 2014.

But instead, Sergio took his "confessions" to the market in 2015 with his presentation Confessions of a Capital Junkie. It was the first time in the automotive industry that an executive of one of the leading groups confessed that most of the activity and capital spending in the industry went exactly nowhere. He ended by quoting the Red Queen from Through the Looking Glass, as he publicly compelled GM, or frankly any other executive, to join him and his team to actually go somewhere.

Source: Confessions of a Capital Junkie

It was another head-scratcher for the industry, for Wall Street, who wanted to know why would he do this?

Because Sergio was a "truth-teller" as John Elkann has said. He cannot sit by and let people continue to go nowhere, when in fact, they could be going a greater distance. "Mediocrity is not worth the trip," Sergio would repeatedly say.

It became such a mantra for myself and for a close friend, Matt Coutts, that he even had the quote monogrammed into the suit he would wear to his most important meetings. Whenever we both would go into some of these most important times of our careers, we've always encouraged the other to "slay like Sergio." It became a mantra for me in yearning to be more, and to build something of meaning.

Unfortunately, for nearly every other executive in the auto industry, mediocrity was comfortable.

Sergio's life was uncomfortable. But as he told his managers and the Chrysler employees, "there is no better life." The life worth living wasn't the easy life, the comfortable life, it was the life that made a difference. A few years later, when Sergio abruptly died in 2018, GM's stock had gone exactly where the Red Queen predicted: nowhere. All that running to go nowhere.

By contrast, FCA and Ferrari (RACE) had indeed gone quite some distance.

The Aftermath

“What matters isn’t being applauded when you arrive—for that is common—but being missed when you leave.” -Baltasar Gracián

Sergio would hide his illness from even those closest to him in his final years -- and would give his life for FCA to achieve the high ambition that he set out for the group -- including, eliminating the debt once and for all.

While the group wouldn't quite hit the 7 million in sales, it would come incredibly close, and would in fact hit the profit target that he set five years before. That was always the more important metric for him to hit from the beginning.

But his life as so much more than what he did -- what he even built.

When news of his irreversible decline came out, on a Saturday morning, it impacted me deeply. I've never had such a strong reaction to a death, except for the passing of my mentor Wally -- who also died at the ominous age of 66, just a couple years before.

My mind in a mess, I walked up 5th Avenue to go visit a place that had frequently gotten me through "the most difficult moments," as Sergio would talk about. I would go to the back right corner of the Met, in the American wing, to see one of the most inspirational paintings of all time: Washington crossing the Delaware.

Source: the Met

The painting isn’t realistic. There were no iceburgs on the Delaware river when Washington crossed --- and frankly, he crossed in the middle of the night, not at sunrise. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were not in the boat.

But while the painting is allegorical and historically inaccurate, there is no better depiction of the adversity that Washington and the founding fathers faced as they birthed a completely new country and told a king he was no longer needed.

The painting captures the big picture, the right brain meaning of the moment -- not the precise recollection of what happened. It's not a photo, and it was never intended to be such. It makes you feel, especially standing in front of its larger-than-life format.

The painting is perfect, because while it shows the courage of Washington, it shows him as the only one in the entire painting that was doing nothing except looking forward. Everyone else is moving, and trudging forward.

As Sergio told his team, there is not just a great man -- there is a Great Group.

I'll never forget the earnings call, which ended up taking place just a few hours after the news of Sergio's passing came out. Normally unemotional characters were in tears.

The CFO could barely make it through the script knowing Sergio was no longer there.

Even Sergio's most adversarial sparring partner, Max Warburton at Bernstein, would write:

"It is clear that many of us in the financial community felt fortunate to have seen Sergio Marchionne at work and to have had the privilege of interacting with him. Certainly, I have never had a closer relationship with a CEO. He is the only CEO who has ever called me on my cell phone, usually to scold me. The only one to offer me unsolicited advice for my life, my family, and my career."

Even his greatest skeptic became his greatest fan, and would proclaim that he was perhaps the best CEO in the history of the auto industry.

He effectively died on the battlefield, working with his team to hit the commitments he made. That morning when CFO Richard Palmer could barely speak the words, he would confirm that for the first time ever, Fiat and Chrysler -- two organizations constantly riddled with massive debt -- were debt free. The organization had hit its commitment to generate €4.7-5.5 billion in net income in 2018 with adjusted net profit of €5.1 billion. It beat its net debt targets by a long-shot.

What was deemed "non-credible" in 2014 was achieved where it mattered.

But far more than being debt-free, and hitting a profit target -- a profit target that (without Ferrari) exceeded the entire market cap of the group less than 7 years before -- Sergio "was a builder," as John Elkann would remember him by.

Sergio's Secret

"The best leaders craft dreams, they propose visions" -Sergio Marchionne

In the wake of Sergio's death, Elkann went from being chairman to being the lead quarterback for the Fiat Galaxy. He became insanely busy, stepping in where Sergio had previously led, trying to find replacements for an irreplaceable builder.

I was only able to catch up with him a year after the event, in Amsterdam, at Exor's annual meeting. Sipping on a tea of Ginger & Lemon, I asked him what Sergio's super-human secret was.

It was one of those moments of clarity that I'll never forget. While the following words aren't exact, it went something like the following:

"Sergio could balance competing dualities like no one else I've seen -- short term action vs. long-term thinking, engineering math vs. advertising emotions, and analysis vs. execution."

Just a half year before, I had the unifying idea for my theory of builders -- that they were the perfect balance between the intellect and emotions, between the left brain efficiency, and right-brain creative possibility. Here, in Amsterdam, the person that was by the side of Sergio the most, was effectively telling me, he was a whole-brained person, and of all the people he's met (most Presidents, some of the most famous investors and CEOs of all time), Sergio was balanced in a way he hadn't seen before.

"There will never be another Sergio," he commiserated.

While Elkann is probably right, he has gone on to articulate this concept of balanced dualities unlike anyone else I've seen in business.

Just a year later, at Exor's first investor day, or the holding company that continues to own the different parts of the Fiat Galaxy, he articulated Exor's values as a balancing of some of these dualities:

Source: Exor 2019 Investor Day Deck

Once John articulated the dualities like this, it was impossible to unsee it.

All of a sudden, all of Sergio's actions made sense.

The contradictions between him and Wall St. made sense.

While Sergio could speak from both his left and his right brain, his rational brain vs. his emotional brain, he would straddle these different characters constantly.

Sergio's Behavioral Dualities

But what he spoke from most, particularly once he had become the dynamic leader of the Fiat Galaxy, he would most often speak from his right brain. How many accountants have you heard say something like the following: "In our dreams, we give life to new realities, where possibilities are endless. If we have the imagination, the power to dream a future as we want it, then we also have the responsibility to realize that dream."

As Jill Bolte Taylor described of her right brain, in Her Stroke of Insight, that is largely where the witness to the voice in our head is. That's more usually correlated to the "Self" vs. the Ego.

When Sergio interviewed you to work inside his galaxy, he would want to know 2 questions: what was your greatest success and what did you really suck at?

The answers would tell him how the person would define success, and he was only looking for those who wanted to make a difference. It would also tell him how honest you were, how humble you were. He was not looking for self-interested people, and wanted people that could check their egos.

“When I meet someone, I don’t have a checklist or a magic recipe. Competences and functional knowledge are a given. I want to know what he fears; I like risk takers. I ask what he is really proud of in his career and what he hates. I want to know his vision about competitors and markets; it is important that someone is not detached from the market and doesn’t insulate himself within the routines of the company.”

So how did this dichotomy play out, for a CEO that would spend 2 months of his year interviewing and coaching thousands of managers?

He would set metric-oriented goals with them (Left-brained planning), but would also judge their leadership skills (right brained qualitative assessment). Very few people, less than 10% would hit the green boxes in the matrix, but still, they would strive for it. It wasn't enough to hit the numbers at all costs -- his managers would have to do it with integrity and with a level of humanness that is rarely emphasized, much less cared for in the corporate world.

Source: HBR Case Study

Sergio was not corporate. He did not rise through the ranks the normal way.

He was unapologetically himself. He never pretended to be anything other than what he was, he never spoke when he didn’t know what he was talking about, and never apologized for being weird and looked at as a black sheep of the industry. He organically grew himself from a rare list of ingredients.

He was a self-professed "capital junkie" but there are no other leaders in the industry that cared more for the workers than he did.

He controversially refused to shut Italian plants during the crisis and instead invested in brands that could sell at high margins and justify the expensive workforce in the US and Italy. He was always willing to talk about bonuses in conjunction with performance. Labor union leaders loved him, and he often cried or teared up giving speeches to the workforce, who largely thought incredibly well of him.

Half the audience at his memorial service were line-workers in their work uniforms- it was amazing the breadth of brands I saw there- Maserati, Ferrari, Alfa, Powertain, Case and New Holland, and of course Fiat.

That was the true testament to what he did -- the feeling he gave everyone he left behind.

How many executives do you know would create such a visceral emotional reaction from all that worked with him? Honestly, it's probably less than 10%, maybe even less than 5%.

How people feel when you die is perhaps the best yardstick to how much you've managed to "make a difference," as Sergio would constantly strive to do.

While he wanted to transform the Fiat galaxy into a €100 billion universe, starting from just above €4 billion, just over a decade before. It happened pretty shortly after his death, with Ferrari alone now worth $75 billion. Ferrari was a rounding error when he joined the group, and it is actually thanks to him and his brilliant invention of the more regular limited edition series, that it has been able to generate the performance that has created so much value.

Stringing together the publicly-traded companies that he over-saw, we can see by the time he got to Fiat, he had already generated a 10x return in 10 years. Not bad. But then he took a collection of assets that nearly everyone had given up on, and brought this career performance to 60x by the time he died.

When he hosted Fiat's 2018 investor day, he knew that his days were numbered. No one, not even his chairman, knew that his health was in such a critical position. So in many ways, the remarks he gave investors is his parting statement of his career -- was likely his parting statement of his life.

He ended where he was most comfortable -- in creative possibility. And in the organization that he built and brought back from the brink.

He recalled a piece from artist Bobby McFerrin, that was scribbled inside of one of his CD's:

"The most difficult thing for the conductor may not be simply getting through the piece with the orchestra still intact but actually having something to say about the music. The composer of classical music puts splotches of ink on paper to suggest to performers what they must do to recreate the sounds heard by the composer in his or her inner ear. The music always exists – even if it’s not being performed at the moment. Some African musicians, however, whose tradition is an oral one, call notated music “paper music.” To capture sound in notation is an odd, abstract idea for people whose music exists because they keep it in their minds and hearts. Like many of the greatest composers – Bach, Beethoven and Mozart, for example – McFerrin is an accomplished improviser and has the ability to reach that place where the joy of making music overcomes the routine of weekly rehearsals and performances of black shorthand symbols on white paper to attempt to reproduce what they think someone else wanted them to say. Then it’s not just paper music: it is music."

One of my favorite photos that emerged of Sergio right as he passed away, which hangs on my office wall, has him seated on a high chair, surrounded by all of the cars and brands that survived because of him. He's like an orchestra conductor, surrounded by his art, or his musicians.

He went on to use the metaphor for the culture that he built -- and that would guarantee the future success of the galaxy that orbited around him.

"We work in an industry where method and process are foundational. There are standard operating procedures, conventional approaches to the way things have always been done, and even conventional approaches to how to address future technology and disruptors.

While we fully understand that processes and procedures are important, at FCA we are, and will always be, about the music. Our approach will be different. Improvisational. Agile. Open to debate. And fearless, born out of humility. We will always be a culture where mediocrity is never, ever worth the trip...

Why are we different and why is it not a temporary or fleeting trait? It is because we are survivors.

The origins of FCA are a group of people from Fiat and Chrysler who faced the most difficult situations in the last ten to fifteen years. They confronted the threat of losing their dignity by losing their work. In some cases, their life’s work, and their family’s work. Survivors remember the courage and resolve to come back from those desperate times, and they apply those same behaviors today.

They pass those traits down, and even though we have employees that have joined our company in the last 5 years, for example, who did not live through the darkest of places, nevertheless, they are reminded and taught through the experiences of the survivors that are distinct to us.

It is this embedded culture, carried by a group of leaders, some of whom you saw today, that survives any single individual at FCA.

Returning back to the analyst comments I referred to earlier. And his question… “Can Marchionne leave a script or instructions”?…

The answer is that there is no script or instructions. Instructions are institutional and temporary.

FCA is a culture of leaders and employees that were born out of adversity and who operate without sheet music.

That is the only way we know.

Thank you all again for coming, and Godspeed to all of us.

Whaou such a great article. I read many investment (related) Substack but yours is amazing.

Thanks for sharing all that including your personal opinion along the way!

Nice job man!